Assembly crash course

Fundamentals

All roads lead to the CPU

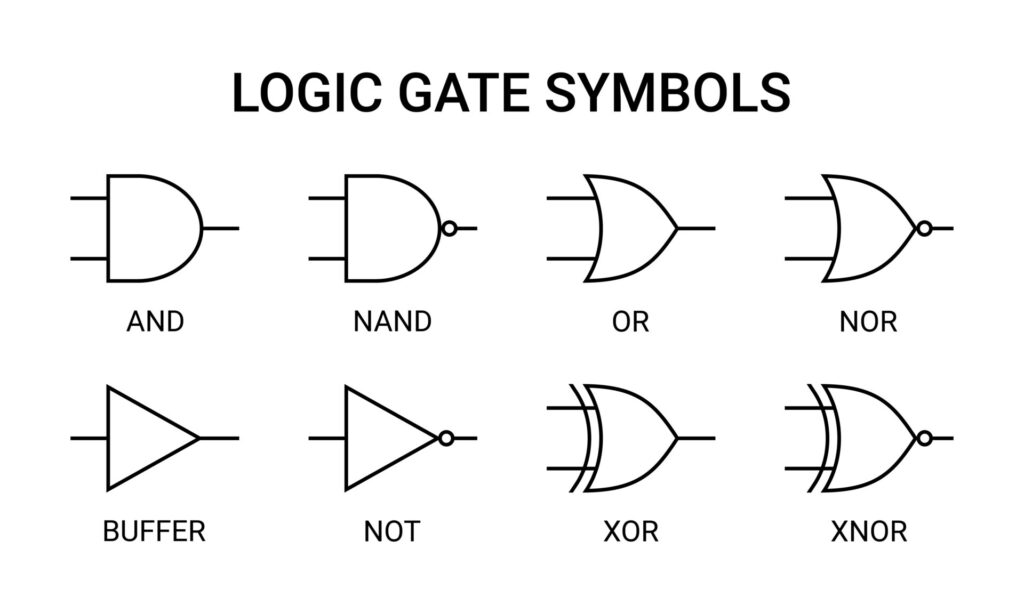

- At the center of the CPU are many many logic gates that computes bits.

- It's all about logic gates

- There are 4 type of logic gates

Assembly

We create a text reppresentation of the binary called Assembly. The binary and assembly code is equivalent. Assembly tell to the CPU what to do, let's lookt an assembly "sentence" in terms of English grammar

- Sentence: We will call this an "instruction" in assembly

- verb: What do you whant the instruction to do? We'll call this an "operation"

- noun: We'll call this an "operand"

Assebly is the simplest programming language, you can mastes asembly in a week.

Noun/Operand

What type of noun might we deal with?? Data!! For the most part, the CPU is concenred whith threee types of data

- data we directly give it as part of the instruction

data that is close at hands

- data saved into register

data in storage

- data saved in memory

Verbs/Operations

What might you want to tell the computer to do with data? Some examples

- add some data together

- sub tract some data

- mul tiply some data

- div ide some data

mov e some data into or out of storage

- mov doen't move the data, it copies it

- cmp (compare) two pieces of data with each other

- test some other proprieties of data

Every architecture has its own variant

- x86 assembly

- arm

Dialects of Assembly

There are two competing Assembly syntaxes for x86:

- Intel (right one)

- AT&T (wrong one)

Data

The CPU only understed one and zero. A binary digit is called bit and numebrs greater than 1 require multiple digits (like numbers greater than 9 for base 10). It's easiest build logic gates that work with 0 and 1. But how a human can interface with the binary? If we use base 2x we can rappresent X binary digits at once!

Expressing text

Bits in a computer typically do something useful (encoding assembly instructions, whole program etc..). The earliest extant text encoding format is ASCII. ASCII has evloved into UTF-8, used on 98% of the web.

Grouping Bits into Bytes

A standard-sized grouping of bits is called a byte. EBCDIC is the 8-bit byte encoding used for the first time in 1963 on IBM terminals.

Grouping Bytes into Words

Bytes are 8-bit, but modern architectures are mostly 64-bit. Word: grouping of 8-bit bytes. Architectur define the word width

- Nibble: half of a byte, 4 bits

- Byte: 1 byte, 8 bits

- Half word / Word: 2 bytes, 16 bits

- Double word (dword): 4 bytes, 32 bits

- Quad word (qword): 8 bytes, 64 bits

Register Arithmetic

Challenges

your first program

Your first register

The CPU thinks in very simple terms. It moves data around, changes data, makes decisions based on data, and takes action based on data. Most of the time, this data is stored in registers.

Simply put, registers are containers for data. The CPU can put data into registers, move data between registers, and so on. These registers, at a hardware level, are implemented using very expensive chips, crammed into shockingly microscopic spaces, and accessed at a frequency where even physical concepts such as the speed of light impact their performance. Hence, the number of registers that a CPU can have is extremely constrained. Different CPU architectures have different amounts of registers, different names for these registers, and so on, but typically, there are between 10 and 20 "general purpose" registers that program code can use for any reason, and up to a few dozen other ones that are used for special purposes.

In x86's modern incarnation, x86_64, programs have access to 16 general purpose registers. In this challenge, we will learn about our first one: rax. Hi, Rax!

rax, a single x86 register, is a tiny piece of the massively complex design of the x86 CPU, but this is where we'll start. Like the other registers, rax is a container for a small amount of data. You move data into rax with the mov instruction. Instructions are specified as an operator (in this case, mov), and operands, which represent additional data (in this case, it will be the specification of rax as a destination, and the value we will want to store there).

For example, if you wanted to store the value 1337 into rax, the x86 Assembly would look like:

mov rax, 1337

You can see a few things:

- The destination (rax) is specified before the source (the value 1337).

- The operands are separated by a comma.

- It is really simple!

In this challenge, you will write your first assembly. You must move the value 60 into rax. Write your program in a file with a .s extension, such as rax-challenge.s (while not mandatory, .s is the typical extension for assembly files), and pass it as an argument to the /challenge/check file (e.g., /challenge/check rax-challenge.s). You can use either your favorite text editor or the text editor in pwn.college's VSCode Workspace to implement your .s file!

ERRATA: If you've seen x86 assembly before, there is a chance that you've seen a slightly different dialect of it. The dialect used in pwn.college is "Intel Syntax", which is the correct way to write x86 assembly (as a reminder, Intel created x86). Some courses incorrectly teach the use of "AT&T Syntax", causing enormous amounts of confusion. We'll touch on this slightly in the next module and then, hopefully, never have to think about AT&T Syntax again

mov rax, 60Your first syscall

So, your first program crashed… Don't worry, it happens! In this challenge, you'll learn how to make your program cleanly exit instead of crashing.

Starting your program and cleanly stopping it are actions handled by your computer's Operating System. The operating system manages the existence of programs and interactions between the programs, your hardware, the network environment, and so on.

Your programs "interact" with the CPU using assembly instructions such as the mov instruction you wrote earlier. Similarly, your programs interact with the operating system (via the CPU, of course) using the syscall, or System Call instruction.

Like how you might use a phone call to interact with a local restaraunt to order food, programs use system calls to request the operating system to carry out actions on the program's behalf. As a bit of an overgeneralization, anything your program does that doesn't involve performing computation on data is done with a system call.

There are a lot of different system calls your program can invoke. For example, Linux has around 330 different ones, though this number changes over time as syscalls are added and deprecated. Each system call is indicated by a syscall number, counting upwards from 0, and your program invokes a specific syscall by moving its syscall number into the rax register and invoking the syscall instruction. For example, if we wanted to invoke syscall 42 (a syscall that you'll learn about sometime later!), we would write two instructions:

mov rax, 42

syscallVery cool, and super easy!

In this challenge, we'll learn our first syscall: exit. The exit syscall causes a program to exit. By explicitly exiting, we can avoid the crash we ran into with our previous program!

Now, the syscall number of exit is 60. Go and write your first program: it should move 60 into rax, then invoke syscall to cleanly exit!

mov rax, 60

syscallExit codes

As you might know, every program exits with an exit code as it terminates. This is done by passing a parameter to the exit system call.

Similarly to how a system call number (e.g., 60 for exit) is specified in the rax variable, parameters are also passed to the syscall through registers. System calls can take multiple parameters, though exit takes only one: the exit code. The first parameter to a system call is passed via another register: rdi. rdi is what we will focus on in this challenge.

In this challenge, you must make your program exit with the exit code of 42. Thus, your program will need three instructions:

- Set your program's exit code (move it into rdi).

- Set the system call number of the exit syscall (mov rax, 60).

- syscall!

Now, go and do it!

mov rdi, 42

mov rax, 60

syscallBuilding executables

So you've written your first program? But until now, we've handled the actual building of it into an executable that your CPU can actually run. In this challenge, you will build it!

To build an executable binary, you need to:

- Write your assembly in a file (often with a .S or .s syntax. We'll use asm.s in this example).

- Assemble your assembly file into an object file (using the as command).

- Link one or more executable object files into a final executable binary (using the ld command)!

Writing assembly. The assembly file contains, well, your assembly code. For the previous level, this might be:

hacker@dojo:~$ cat asm.s

mov rdi, 42

mov rax, 60

syscallBut it needs to contain just a tad more info. We mentioned that we're using the Intel assembly syntax in this course, and we'll need to let the assembler know that. You do this by prepending a directive to the beginning of your assembly code, as such:

.intel_syntax noprefix

hacker@dojo:~$ cat asm.s

mov rdi, 42

mov rax, 60

syscall.intel_syntax noprefix tells the assembler that you will be using Intel assembly syntax, and specifically the variant of it where you don't have to add extra prefixes to every instruction. We'll talk about these later, but for now, we'll let the assembler figure it out!

Assembling object files! Next, we'll assemble the code. This is done using the assembler, as, as so:

hacker@dojo:~$ ls

asm.s

hacker@dojo:~$ cat asm.s

.intel_syntax noprefix

mov rdi, 42

mov rax, 60

syscall

hacker@dojo:~$ as -o asm.o asm.s

hacker@dojo:~$ ls

asm.o asm.s

hacker@dojo:~$Here, the as tool reads in asm.s, assembles it into binary code, and outputs an object file called asm.o. This object file has actual assembled binary code, but it is not yet ready to be run. First, we need to link it.

Linking executables. In a typical development workflow, source code is compiled and assembly is assembled to object files, and there are typically many of these (generally, each source code file in a program compiles into its own object file). These are then linked together into a single executable. Even if there is only one file, we still need to link it, to prepare the final executable. This is done with the ld (stemming from the term "link editor") command, as so:

hacker@dojo:~$ ls

asm.o asm.s

hacker@dojo:~$ ld -o exe asm.o

ld: warning: cannot find entry symbol _start; defaulting to 0000000000401000

hacker@dojo:~$ ls

asm.o asm.s exe

hacker@dojo:~$Assembly crash course

indirect jump

The last jump type is the indirect jump, often used for switch statements in the real world. Switch statements are a special case of if-statements that use only numbers to determine where the control flow will go.

switch(number):

0: jmp do_thing_0

1: jmp do_thing_1

2: jmp do_thing_2

default: jmp do_default_thingThe switch in this example works on number, which can either be 0, 1, or 2. If number is not one of those numbers, the default triggers. You can consider this a reduced else-if type structure. In x86, you are already used to using numbers, so it should be no surprise that you can make if statements based on something being an exact number. Additionally, if you know the range of the numbers, a switch statement works very well. Take, for instance, the existence of a jump table. A jump table is a contiguous section of memory that holds addresses of places to jump. In the above example, the jump table could look like:

[0x1337] = address of do_thing_0

[0x1337+0x8] = address of do_thing_1

[0x1337+0x10] = address of do_thing_2

[0x1337+0x18] = address of do_default_thingUsing the jump table, we can greatly reduce the amount of cmps we use. Now all we need to check is if number is greater than 2. If it is, always do:

jmp [0x1337+0x18]Otherwise:

jmp [jump_table_address + number * 8]Using the above knowledge, implement the following logic:

if rdi is 0:

jmp 0x40301e

else if rdi is 1:

jmp 0x4030da

else if rdi is 2:

jmp 0x4031d5

else if rdi is 3:

jmp 0x403268

else:

jmp 0x40332cPlease do the above with the following constraints:

- Assume rdi will NOT be negative.

- Use no more than 1 cmp instruction.

- Use no more than 3 jumps (of any variant).

- We will provide you with the number to 'switch' on in rdi.

- We will provide you with a jump table base address in rsi.

.intel_syntax noprefix

.global _start

_start:

cmp rdi, 0x3

jg default

mov rax, [rsi + rdi * 8]

jmp rax

default:

mov rax, [rsi+32]

jmp raxaverage loop

In a previous level, you computed the average of 4 integer quad words, which was a fixed amount of things to compute. But how do you work with sizes you get when the program is running?

In most programming languages, a structure exists called the for-loop, which allows you to execute a set of instructions for a bounded amount of times. The bounded amount can be either known before or during the program's run, with "during" meaning the value is given to you dynamically.

As an example, a for-loop can be used to compute the sum of the numbers 1 to n:

sum = 0

i = 1

while i <= n:

sum += i

i += 1Please compute the average of n consecutive quad words, where:

- rdi = memory address of the 1st quad word

- rsi = n (amount to loop for)

- rax = average computed

.intel_syntax noprefix

.global _start

_start:

xor rbx, rbx

xor rax, rax

loop_start:

cmp rbx, rsi

jle loop_core

mov rcx, rsi

div rcx

jmp loop_end

loop_core:

add rax, [rdi + rbx * 8]

inc rbx

jmp loop_start

loop_end:

nopcount_non_zero

In previous levels, you discovered the for-loop to iterate for a number of times, both dynamically and statically known, but what happens when you want to iterate until you meet a condition? A second loop structure exists called the while-loop to fill this demand. In the while-loop, you iterate until a condition is met.

As an example, say we had a location in memory with adjacent numbers and we wanted to get the average of all the numbers until we find one bigger or equal to 0xff:

average = 0

i = 0

while x[i] < 0xff:

average += x[i]

i += 1

average /= iUsing the above knowledge, please perform the following:

Count the consecutive non-zero bytes in a contiguous region of memory, where:

- rdi = memory address of the 1st byte

- rax = number of consecutive non-zero bytes

Additionally, if rdi = 0, then set rax = 0 (we will check)!

An example test-case, let:

rdi = 0x1000 [0x1000] = 0x41 [0x1001] = 0x42 [0x1002] = 0x43 [0x1003] = 0x00

.intel_syntax noprefix

.global _start

_start:

xor rax, rax

xor rbx, rbx ; i = 0

cmp rdi, 0x0

jg start_loop

jmp end_loop

start_loop:

cmp byte ptr [rdi + rbx], 0

jne core_loop

jmp end_loop

core_loop:

inc rax

inc rbx

jmp start_loop

end_loop:

nopstring_lower

In this level, you will be provided with a contiguous region of memory again and will loop over each performing a conditional operation till a zero byte is reached. All of which will be contained in a function!

A function is a callable segment of code that does not destroy control flow.

Functions use the instructions "call" and "ret". The "call" instruction pushes the memory address of the next instruction onto the stack and then jumps to the value stored in the first argument.

Let's use the following instructions as an example:

0x1021 mov rax, 0x400000 0x1028 call rax 0x102a mov [rsi], rax

- call pushes 0x102a, the address of the next instruction, onto the stack.

- call jumps to 0x400000, the value stored in rax.

The "ret" instruction is the opposite of "call".

ret pops the top value off of the stack and jumps to it.

Let's use the following instructions and stack as an example:

Stack ADDR VALUE 0x103f mov rax, rdx RSP + 0x8 0xdeadbeef 0x1042 ret RSP + 0x0 0x0000102a

Here, ret will jump to 0x102a.

Please implement the following logic:

str_lower(src_addr):

i = 0

if src_addr != 0:

while [src_addr] != 0x00:

if [src_addr] <= 0x5a:

[src_addr] = foo([src_addr])

i += 1

src_addr += 1

return ifoo is provided at 0x403000. foo takes a single argument as a value and returns a value.

All functions (foo and str_lower) must follow the Linux amd64 calling convention (also known as System V AMD64 ABI): System V AMD64 ABI

Therefore, your function str_lower should look for src_addr in rdi and place the function return in rax.

An important note is that src_addr is an address in memory (where the string is located) and [src_addr] refers to the byte that exists at src_addr.

Therefore, the function foo accepts a byte as its first argument and returns a byte.

.intel_syntax noprefix

.global str_lower

mov r8, 0x403000

str_lower:

xor rbx, rbx

cmp rdi, 0

jmp end

loop:

mov rcx, rdi

xor rdi, rdi

mov dil, byte ptr [rcx]

cmp dil, 0x00

je end

cmp dil, 0x5a

jg greater

call r8

mov byte ptr [rcx], al

greater:

mov rdi, rcx

inc rdi

jmp loop

end:

mov rax, rbx

retmost common bytes

In the previous level, you learned how to make your first function and how to call other functions. Now we will work with functions that have a function stack frame.

A function stack frame is a set of pointers and values pushed onto the stack to save things for later use and allocate space on the stack for function variables.

First, let's talk about the special register rbp, the Stack Base Pointer.

The rbp register is used to tell where our stack frame first started. As an example, say we want to construct some list (a contiguous space of memory) that is only used in our function. The list is 5 elements long, and each element is a dword. A list of 5 elements would already take 5 registers, so instead, we can make space on the stack!

The assembly would look like:

; setup the base of the stack as the current top mov rbp, rsp ; move the stack 0x14 bytes (5 * 4) down ; acts as an allocation sub rsp, 0x14 ; assign list[2] = 1337 mov eax, 1337 mov [rbp-0xc], eax ; do more operations on the list ... ; restore the allocated space mov rsp, rbp ret

Notice how rbp is always used to restore the stack to where it originally was. If we don't restore the stack after use, we will eventually run out. In addition, notice how we subtracted from rsp, because the stack grows down. To make the stack have more space, we subtract the space we need. The ret and call still work the same. Consider the fact that to assign a value to list[2] we subtract 12 bytes (3 dwords). That is because stack grows down and when we moved rsp our stack contains addresses <rsp, rbp). Once again, please make function(s) that implement the following:

most_common_byte(src_addr, size):

i = 0

while i <= size-1:

curr_byte = [src_addr + i]

[stack_base - curr_byte * 2] += 1

i += 1

b = 0

max_freq = 0

max_freq_byte = 0

while b <= 0xff:

if [stack_base - b * 2] > max_freq:

max_freq = [stack_base - b * 2]

max_freq_byte = b

b += 1

return max_freq_byteAssumptions:

- There will never be more than 0xffff of any byte

- The size will never be longer than 0xffff

- The list will have at least one element

Constraints:

- You must put the "counting list" on the stack

- You must restore the stack like in a normal function

- You cannot modify the data at src_addr

.intel_syntax noprefix

.global most_common_byte

most_common_byte:

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

sub rsp, 512 ; 256 words for histogram

mov r9, rsp ; r9 = histogram base

xor rbx, rbx ; i = 0

extern_while:

cmp rbx, rsi ; while (i < size)

jg greater

movzx rcx, byte ptr [rdi + rbx] ; curr_byte

inc word ptr [r9 + rcx*2] ; histogram[curr_byte]++

inc rbx

jmp extern_while

greater:

xor rax, rax ; result = 0 (most common byte)

xor rbx, rbx ; b = 0

xor rcx, rcx ; max_freq = 0

inner_while:

cmp rbx, 255

jg inner_greater

mov dx, word ptr [r9 + rbx*2]

cmp dx, cx

jle no_update

; update max

mov cx, dx ; max_freq = histogram[b]

mov rax, rbx ; result = b

no_update:

inc rbx

jmp inner_while

inner_greater:

mov rsp, rbp

pop rbp

ret